For years, “secure hosting” has been treated as a given in the hosting industry. It appears everywhere: product pages, comparison tables, sales decks. The implicit message is simple – if you host your WordPress site on a serious provider, security is largely handled.

Patchstack, a security company focused on real WordPress threat prevention published results of the security case study and they show how far that assumption is from reality.

The short version: most real attacks still work.

Our role in the study

Patchstack made a good call not to run this study in isolation and invited external industry observers to review the scope, methodology, and interpretation of results, to avoid turning the whole thing into a vendor-centric security exercise.

Konrad Keck, co-founder of webhosting.today, participated in the study to help ensure the results were interpreted in a way that reflects how hosting environments actually operate in practice.

This was not a theoretical test

Patchstack did not run simulations or synthetic benchmarks.

They deployed clean WordPress installations, installed known vulnerable versions of popular plugins, and executed real exploits that are actively used in the wild. No zero-days. No obfuscation. No “advanced attacker” scenarios.

Just the same attacks that hit customer sites every day.

On the hosting side, standard security layers were enabled – firewalls, WAFs, server-level protections. Exactly what many providers sell under the label “secure hosting”.

The number that matters: ~26%

Across all tests, hosting environments blocked only about 25.89% of exploit attempts.

That means roughly 74% of real attacks succeeded.

Not partially. Not “logged but allowed”. They succeeded in ways that matter: unauthorized actions, code execution, account takeover.

If you are wondering why customers keep getting hacked despite “all security enabled”, this is your answer.

Where it breaks completely: admin takeover

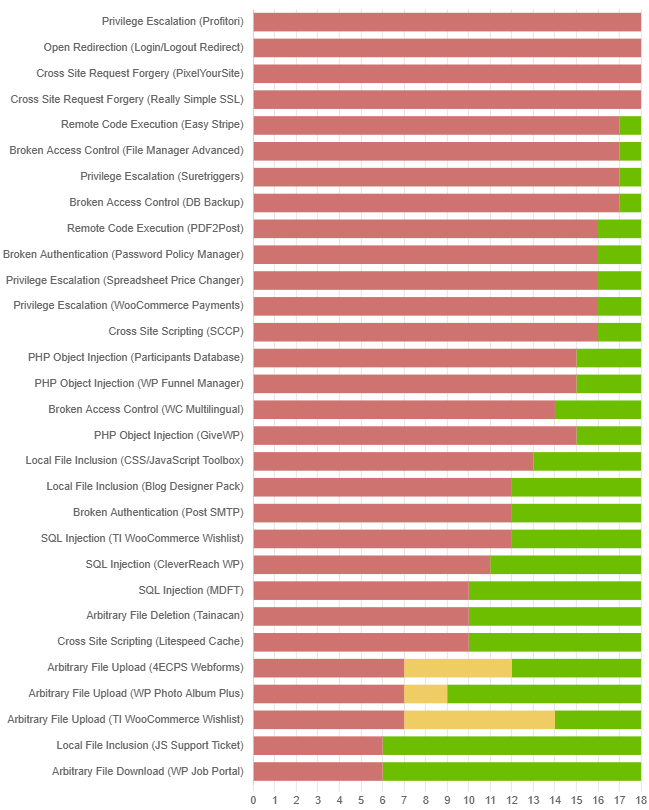

The worst results appeared in privilege escalation vulnerabilities – attacks that end with the attacker becoming a WordPress administrator.

Hosting-side security stopped only around 12% of these attacks.

In other words: when an exploit leads to full control of a site, the hosting layer usually does nothing.

These are not edge cases. These are the incidents that turn into emergency restores, angry phone calls, churn, and “we’re moving away” emails.

Why hosting security can’t see these attacks

This is not about bad intentions or lazy providers. It’s about architecture.

Most hosting security operates at the infrastructure level. It looks for suspicious request patterns, known signatures, abnormal traffic, or filesystem abuse. That works reasonably well for classic problems like malicious file uploads – which is why those were blocked more often, at around 60%.

Modern WordPress exploits don’t look like classic attacks.

They abuse application logic: permissions, roles, missing checks, broken workflows inside plugins. From the outside, the HTTP request looks valid. The firewall sees nothing unusual. WordPress executes it. The exploit works.

Without understanding WordPress context, hosting security is blind.

“Secure hosting” has become a marketing label

One uncomfortable takeaway from this study is how meaningless the term “secure hosting” has become.

Different providers use different tools, configurations, and rule sets, yet all describe them in the same way. Two hosts can claim identical security while delivering radically different outcomes — or no real protection at all.

For customers, this creates a false sense of safety. For providers, it creates a growing gap between promise and reality.

The business implication is simple

This study does not say hosting providers must solve WordPress security on their own.

It says something more fundamental: generic infrastructure security is not enough, and pretending otherwise damages trust.

If three out of four real exploits still work, then “secure hosting” is not a feature – it’s a slogan.

And attackers are very happy that the industry still treats it that way.

Damian Andruszkiewicz

Author of this post.