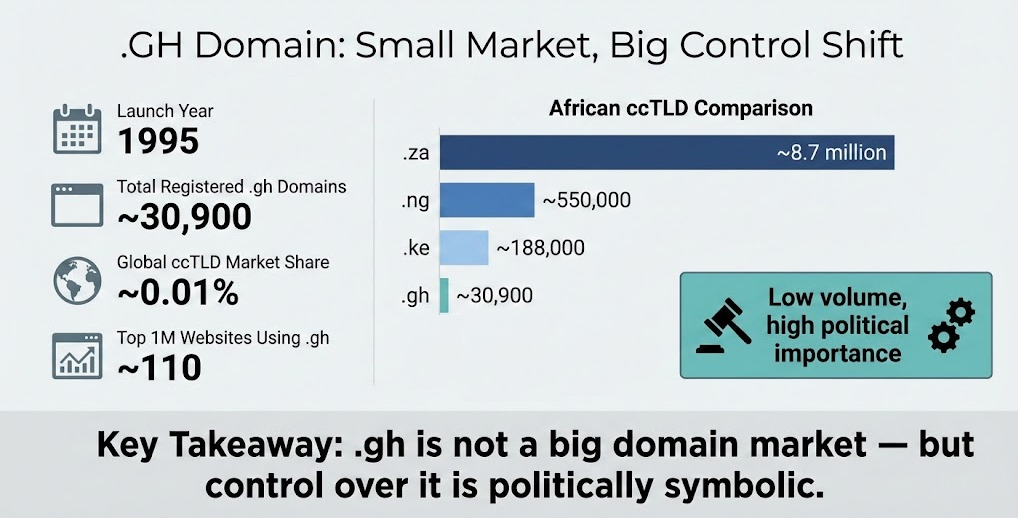

TL;DR – Ghana’s government wants full control of the .gh country-code domain. After nearly 30 years of private operation, the state is moving to nationalize it. This isn’t just a local political story but another clear signal that governments are reasserting control over internet naming infrastructure.

If you sell domains, run registrars, or depend on ccTLD stability, this matters.

What happened

The government of Ghana announced plans to move the .gh ccTLD fully under state ownership. The domain has been run since the mid-1990s by a private operator controlled by Nii Quaynor, a former board member of ICANN.

A law passed in 2008 already called for nationalization, but the handover stalled for years due to financial disagreements.

The private operator reportedly wants 10% of future .gh domain revenue paid indefinitely to the local Internet Society chapter and the government says no.

The Minister of Communication is now publicly pushing the takeover and talking about giving .gh or .com.gh domains for free to newly registered companies.

No subtlety here, only a clear message: this is state property now.

Why this is happening now

This move fits a broader global trend dressed up as “digital sovereignty.” Governments increasingly view ccTLDs as national assets and political symbols of online identity.

What changed is the tone. Ghana’s officials are no longer negotiating quietly, but stating ownership as a fact.

The timing also matters because governments are more comfortable intervening in internet infrastructure than they were 10–15 years ago. Also ICANN’s historical preference for “consent of the incumbent” (that current operator has to agree before control is taken away) is getting weaker when states push hard enough.

Finally, emerging markets, such as Ghana are less tolerant of long-standing private control arrangements made in the early internet era and this is not an isolated case.

Similar moves that already happened and warning signs in other countries

- Nigeria – .ng was moved from an academic/private setup to a government-backed structure (NiRA),

- Kenya – .ke shifted from university control to KENIC, with strong government oversight,

- India – .in is formally operated by NIXI that is government-linked,

- Brazil – .br is run by CGI.br (multi-stakeholder, but state-dominated),

- Indonesia – the government increasingly talks about digital sovereignty and ccTLD governance tightly aligned with national policy.

- Vietnam – .vn fully state-run via VNNIC, domains treated as national infrastructure, not a market product.

Why this matters to hosting and domain businesses

1. ccTLD risk is not theoretical anymore

If you rely on ccTLDs in Africa, Asia, or LATAM, assume that long-term private management is politically fragile. Contracts signed in the 1990s don’t mean much once governments decide otherwise.

2. “Free domains” distort the market

Giving .gh or .com.gh domains to newly registered companies sounds good politically but it undercuts commercial registrars, devalues domains as products and pushes costs downstream (renewals, hosting, upsells).

This is not pro-market behavior.

3. ICANN won’t save you

ICANN traditionally avoids redelegation fights, but when a government insists, ICANN usually follows the political reality. If your ccTLD business model depends on ICANN being a shield, that’s a weak defence.

4. Local registrars may win, foreign ones may lose

A state-controlled registry can favor domestic registrars, rewrite pricing and access rules and finally change EPP policies with limited notice

If you’re selling ccTLDs cross-border, this is a serious risk.

This fits a clear pattern governments reclaiming ccTLDs, with “national identity” used as justification, where commercial logic is replaced by political logic

Expect more of this especially where ccTLDs are still meaningful locally (unlike many European markets).

What you should consider now

If you’re in domains:

- treat ccTLD exposure as geopolitical risk, not just registry risk,

- avoid over-reliance on a single country registry,

- watch for “free domain” programs – they kill ARPU fast.

If you’re in hosting:

- expect short-term domain growth, long-term pricing chaos,

- prepare for policy changes with zero notice,

- build bundles that don’t depend on ccTLD margin.

If you invest or acquire:

- discount ccTLD revenue where state ownership is plausible,

- assume rules can change mid-cycle,

- your due diligence should include political intent.

Bottom line

Ghana taking back .gh isn’t about one man or one registry. It’s about governments showing the industry who they think owns the internet inside their borders. If your strategy assumes ccTLDs are like neutral commercial assets, better update that assumption.

Damian Andruszkiewicz

Author of this post.